Indigenous Biocultures and Rights of Nature in Uganda

Dennis Tabaro is an environmental activist, agroecologist, Earth Jurisprudence practitioner and Expert Member of UN Harmony with Nature Initiative. As a founder and executive director of the African Institute for Culture and Ecology (AFRICE), he coordinates activities on Rights of Nature and indigenous people’s knowledge and culture in Uganda.

Questions by Imke Horstmannshoff

IH: What is your own and AFRICE' vision of Rights of Nature?

Rights of Nature are inextricably connected with human rights. As humans, it is the harmony with Nature, being part of it and inextricably connected with it, that enables our enjoyment of our rights.

This includes the right to enjoy, access and utilize the gifts of Nature if - and only if - we recognise, respect and protect the Rights of Nature.

Our vision of Rights of Nature at AFRICE, therefore, is that of communities living in harmony with Nature in order to attain their rights. This vision started do develop in early 2013 when I started a journey to indigenous communities, with the aim to discuss and understand their views and bio cultures.

Rights of Nature, i.e. rights to evolve, co-create and regenerate, are manifested in the way animals, birds, plants, insects, air, soil, water and all life systems therein are allowed to enjoy their existence, prosperity, interrelationship and co-existence. These rights are fully realized and respected in those areas called ‘Sacred Natural Sites’ (SNS) or ‘Mpuluma’, where Nature is valued and protected by indigenous communities.

Who are the people you met?

They are the Bagungu, Banyabutumbi, BaSsese and Batwa indigenous communities, living along the great lakes of Mwitanzige (Albert), Rweeru (Edward) Nalubaale (Victoria) and Bwindi impenetrable forest, in Uganda. Regular and deeper dialogue with these communities, especially with the Bagungu, led me to learn about their traditional cultures and how they are related and interconnected with Nature (bioculture) and the transcendent (spirituality). The Ugandan experience and that of other indigenous communities around the world, save for the influence of colonial powers and current developments, has confirmed our assertion that...

...when communities exercise their rights to fulfill this relationship, Rights of Nature are protected.

How did you work together with them for the implementation of RoN in Uganda?

AFRICE has facilitated the Bagungu process of reviving and strengthening their custodianship of SNS as a way to protect their bioculture and consequently Rights of Nature. In doing so, we contributed to the recognition of SNS, as well as to the drafting of the Ugandan Rights of Nature law.

With support from the Gaia Foundation (UK), AFRICE mobilized and worked closely with the Bagungu custodians of SNS (locally called ‘Balamansi’) to pursue a process of reviving their customary governance systems. This took some years as AFRICE had to identify the true custodians and to gain their trust – they had been ridiculed, persecuted and stigmatized as ‘satanic’ by Christian missionaries, colonizers and other groups for a long time. After some exploration, one of the custodians, Kagole Margret, agreed with a few others to work with AFRICE (still not willing to be publicly identified as custodians at the time, for fear of reaction from the community).

Later, in 2015, Kagole was supported by Gaia Foundation and the African Biodiversity Network to attend a gathering of African custodians of SNS in Ethiopia. It was at this meeting where the custodians made a call to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR), urging for recognition of SNS and their custodian communities in Africa. In 2017, this call was launched in Uganda by the then Chairperson of the Uganda Human Rights Commission, late Medd Kaggwa. Upon its receipt, the African Commission, on its 60th Session in Niger, crafted and passed the ‘Resolution recognising Sacred Natural Sites and Territories’; now known as ACHPR Resolution 372.

Taking this inspiration from custodians’ successes home, Kagole and the few other custodians she had gathered were motivated to be bolder. Their custodian dialogues grew from a small group of 6 to a gathering of 20 custodians and clan leaders from 10 clans, meeting every month during 2017.

They discussed ways to re-weave the basket of the Bagungu traditional culture, strengthening their ritual performances around their SNS and territories and reviving their traditional seed diversity needed for the rituals in the SNS.

These rituals represent the only way sacred sites are being kept potent and powerful. They are performed by using indigenous seeds (both crop and animal seeds). The emphasis here was to encourage custodians to perform such rituals in their respective sites.

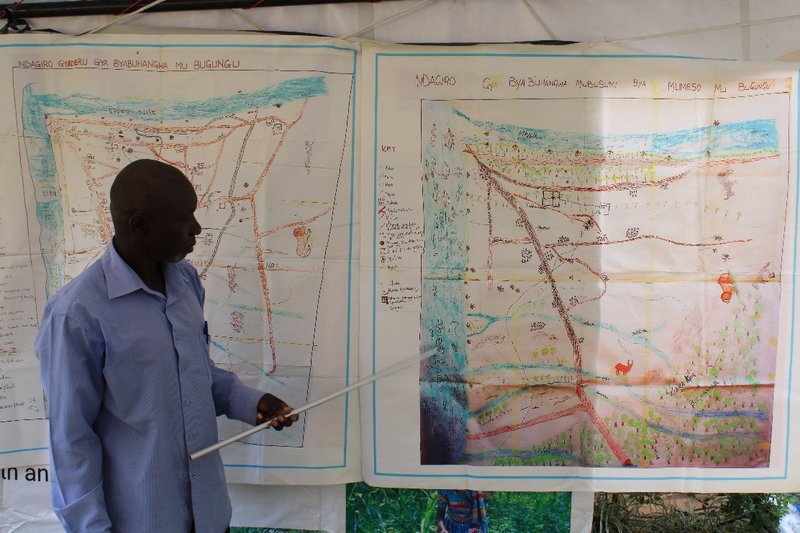

In 2017, the custodians launched their first eco-cultural mapping processes. Led by older custodians and clan heads, they drew the ancestral map of the past, a map of the current showing what was happening now, and a map of their desired future. The women custodians of seed diversity also developed the Ancestral Calendar of the past, the present and future. This mapping and calendar process showed them how much they had lost over the years and helped them to plan on how the old order could be restored.

It also helped them to develop a collective picture of the order of their land and the seasonal cycles, thus remembering more and more traditions, seeds, seasonal indicators from their territory and customary laws as they drew and studied the maps together.

In 2019, Uganda passed the law on Rights of Nature. How did this law come about, and what does it entail?

This law, which is the first of its kind in Uganda and Africa, was spearheaded by a group of lawyers, the Advocates for Natural Resources and Development (ANARDE) at the parliamentary level. In the meantime, AFRICE was working at the community level to provide ground evidence of the SNS, including different ecosystems and natural entities involved, as well as human custodians who could represent Nature in courts of law.

The passing of this law gave more momentum to our work on the ground. It was a confirmation and conviction to the communities that their rights were being recognized. The law enabled custodians to regulate access to different areas, such as – in the case of the Bagungu – fishing in ItakaMwitanzige (Lake Albert), in order to respect the life cycle of the Lake and the fish. When these rules are followed, there is enough for everyone who depends on the Lake, including other-than-human species. Only when they are respected, would sanity come back to the Lake and to those dependent on it – including its traditional name (Mwitanzige).

Meanwhile, women elders, who hold the seed knowledge, have organized to revive this knowledge of identifying, growing and storing indigenous seed varieties for further multiplying and sharing. Like in other indigenous communities, for the Bagungu, a seed is endorsed with a cultural meaning and thus forms part of a deep connection with Nature: Custodians of SNS use indigenous seeds to perform rituals and other traditional ceremonies for food, social and many cultural functions.

What are the legal mechanisms to enforce these customary laws?

These customary laws have since been documented and presented to the Buliisa District Council, which issued a resolution for recognizing them as laws for protecting the SNS in Buliisa. However, this resolution was not legally binding to guarantee proper protection of SNS and the custodians.

We agreed that there was a need for making a bill for a protection ordinance of SNS and ecosystems.

In 2021, after passing the draft bill to the council and its committees and after holding district-wide multi-stakeholder consultations, Buliisa made yet another historic step by passing a bill for a protection ordinance of SNS and ecosystems. The bill was presented to the office of the Attorney General, the 1st Parliamentary Council of the Uganda Parliament, for approval.

We are now in the process of clearly specifying different customary laws for protecting Nature (the lakes, rivers, forests, animals, insects) as stipulated by the ordinance bill. Meanwhile, the Bagungu have developed clan structures (including custodians and women elders), for restorative justice where violators of Rights of Nature are punished and made to restore, atone or compensate for the violation of nature’s rights.

The Rights of Nature enacted by the Ugandan Parliament is yet to be implemented, but there is no specific legal framework to do this. We are working with other groups of civil society to come up with a draft legal framework and policy proposals to present to the government for consideration.

Where do you see challenges for the implementation of Rights of Nature in Uganda?

The journey to protect the Rights of Nature is not an isolated, conventional work, by either government or civil society. It is a commitment, a calling, a dedicated, decolonising process. This kind of awareness is yet to arise and it takes resources. In the process of colonization, British colonizers introduced foreign religion and an education system, which stigmatized the traditional cultures and weakened their biocultural systems that enabled their close connection with Nature.

”Nabunu twijwiire obunaku,hakuba ensi yabugungu erimukucura. Tukaba tutikarolagaga endwiire nkazinu,okubura encu mu itaka Mwitanzige", states Aron Kiiza, 85 years, a chief custodian of one of the SNS:

“Even now we are sorrowful, because the land of Bugungu is all mourning. We had never seen diseases like these and lack of fish in Lake Mwitanzige.”

While the Parliament has passed the National Environmental Act, the responsible government minister is yet to provide regulations for its implementation. Given this background, however, there is a need for a lot of sensitization and engagement by the communities and civil society. To be very honest, there are just a few non-governmental organizations and communities like the Bagungu, who follow this approach of promoting customary governance systems for the realization of Rights of Nature.

Related to the above, colonization in Africa and elsewhere has taken its toll on people’s rights to their culture, including bioculture. We must decolonize conservation policies, the legal and religious systems that are now leading to biodiversity loss, food loss and loss of entire ecosystems. It starts with appreciating the fact that humans are not superior to Nature; that where humans get their rights is where Nature gets its rights.

Moreover, protection of SNS is a systems approach: It must be seen as an integral part of preserving fauna and flora; conservation of animal habitats and biodiversity, indigenous food systems and regenerative food and ecosystems for sustainable living; a process that translates into recognition of Rights of Nature. However, SNS in Uganda are yet to be understood by a larger majority of the people, most of whom are not familiar with the concept. Many people know SNS only as places for pagans and witchcraft, which are not worthwhile protecting.

The industrial farming systems, coupled with hybrid seeds and genetically engineered seeds monocultures, chemical pests and fertilizers, is destroying soils and all biodiversity. This poses a big threat and thus a big challenge to the implementation of Rights of Nature. The traditional farming systems, embedded in agroecology, were very conscious about all forms of Nature and the relationship between Nature and farming, fishing, hunting and food gathering. A holistic food and ecological governance approach will be an effective way to realize Rights of Nature.

As Gafabusa John, the Chairman of the Association of Custodians of Sacred Natural Sites in Buliisa, states:

“We hope the Government will quickly approve the ordinance on protection of our Sacred Natural Sites so that our rivers, forests and entire land scape with animals can be protected. We need also to have this law in place so that we can have the strength and courage to train our sons before we leave this world.”

Literature & Links

- Q&A: African Commission’s new Resolution (372) on Sacred Natural Sites and Territories: https://gaiafoundation.org/qa-african-commissions-new-resolution-372-on-sacred-natural-sites-and-territories/

- Baliisa District Council: Resolution recognizing the Customary Law of the Bagungu Custodian clans. Online: http://files.harmonywithnatureun.org/uploads/upload989.pdf – noting “the concern of the Bagungu clan leaders for Butoka (Mother Earth) and for the future generations of all species of the Earth”, and their “ancestral responsibility to protect the well-being of their land, and of the planet”.